WID Reporting of the Biafran Airlift

From Rpcvdraft

The World Is Deep - Continued

Reporting of the Biafran Airlift David L. Koren, Nigeria 9 (1963-1966) March 2007

The four of us UNICEF volunteers took turns flying into Biafra. We would go in with the first plane, help with the unloading, and come out with the last flight. Those who stayed in Sao Tome helped load the planes. Between the four of us, we knew what the planes were carrying. One day I was lying on my bed listening to a BBC broadcast. It was a lengthy report about the Biafran airlift. The report described how the churches were using the cover of relief flights to smuggle arms to the Biafran army. The reporter read lists from the cargo manifests of all the guns and ammunition. He had details, like the make and model numbers of the weapons, and the tonnage, and he gave the dates and the aircraft on which they were flown. Those were my planes, and I was on duty those days. I put the cargo on those planes in Sao Tome or took it off in Biafra, and I never saw a single weapon. Not those days or any other.

I had always heard, and believed, that the BBC was the world standard in journalism for accurate and unbiased reporting.

My first landing in Biafra was uneventful, but emotional. The night air was fresh and tropical and familiar. It felt, in a sense, like coming home.

The airstrip was indeed a road. It was not flat, but slightly undulating. The wings extended over the edges of the pavement. “So this is Airstrip Annabelle,” I said.

“How did you know that?” asked the captain. “That’s supposed to be a military secret.”

“I read it in the New York Times.”

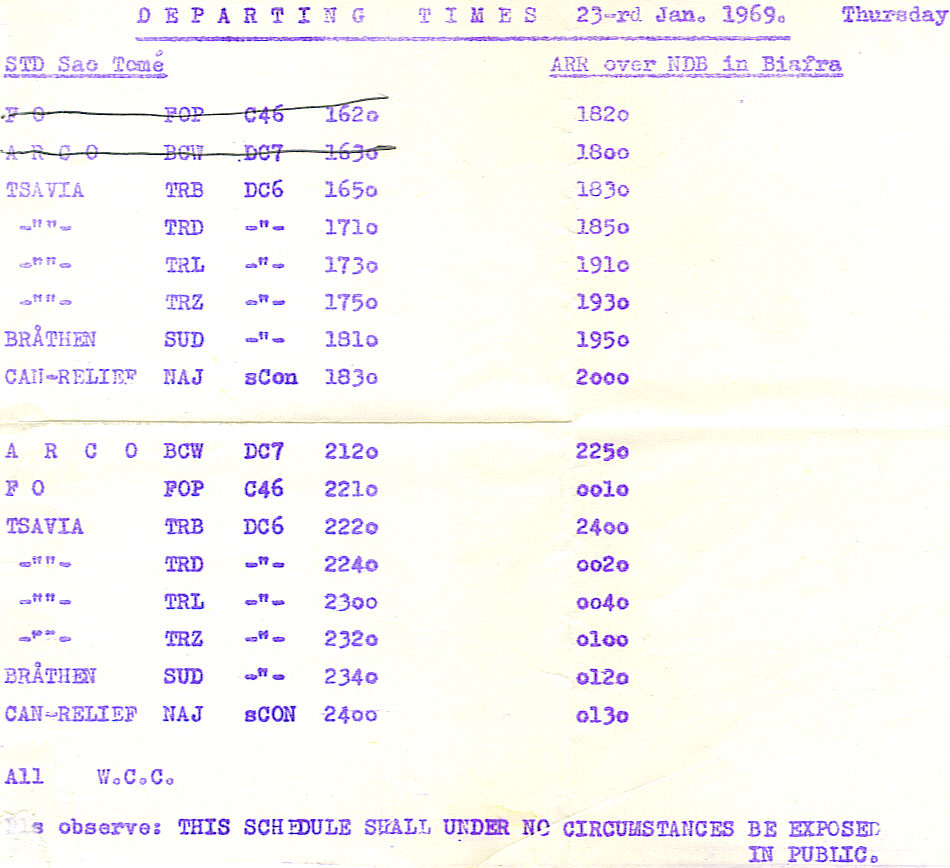

A flight schedule was published every day listing the planes and their arrival times over the beacon in Biafra. At the bottom of the schedule was a notice: “THIS SCHEDULE SHALL UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES BE EXPOSED IN PUBLIC.” But everybody had a copy; it defined our evening’s entertainment. We called it TV Guide. Because we were flying into a war zone, some security was required. However, things were pretty lose, and it would have been easy for a reporter to get information about what was going on. It’s not surprising that the NY Times knew about Airstrip Annabelle.My job was to get the planes unloaded and turned around for another load. I don’t know what I thought that meant – making people work faster? But it turned out not to be necessary. The workers who unloaded the plane were tired, hungry Biafran soldiers who worked as fast as they could. So I just helped move the sacks closer to the door. After the first plane was unloaded I got down and waited in the night for the next plane to arrive. Sometimes the wait would be a couple of hours as the first wave of planes returned to Sao Tome for a second run. It was kept very dark. If someone showed a light, even briefly, there were shouts from unseen soldiers all around, “Off de light! Off de light!” Because of the bomber.

Out of the night someone would quietly approach me and begin a conversation. We would exchange information about ourselves, where we were from, what we did before the war. As the four of us made repeated trips we developed our own regular contacts. They would find us in the dark. This led to some personal trading. Personal care items like soap were a tradable commodity, and a carton of American cigarettes was very valuable. I traded for Biafran souvenirs, such as a drum, ekwe, and High Life records – I got a “Baby Pancake.”

When the second wave of planes was due we often heard the bomber cruising overhead. My contact showed me where the bunkers were, next to the unloading bays. If the bombs started falling we were to dive into the bunkers. He told me he had watched planes bombing in Umuahia, with a kind of fascination, while a friend urged him to get in the bunker. “Take cover before they give cover.”

When the bombs started falling you could hear them screaming down. After some experience with this it became possible to tell by the Doppler shift and intensity of the scream whether a bomb was going away from you or coming toward you and about how much time you had before it got there. One night after I had unloaded the first plane and climbed into the second one, the bombs came. The air crew and the soldiers who had been gathering outside the plane went for the bunker. By the sound I knew that the bomb was coming my way, and I judged that I didn’t have time to climb down the ladder and get to shelter. It was coming right now. There were sacks of CSM piled neatly on either side of a narrow isle in the center of the plane and I dove in there, hoping they might absorb some of the shrapnel. The blast shook the plane and deafened me, but we escaped damage. The next day on Sao Tome, I walked around the plane for a closer inspection. I found a few hits, one near a tire, but none more than nicks or scratches.

Immediately after that bomb went off, a second one hit further down the runway. We kept unloading the second plane as the first plane, which I had come on, was preparing to take off. I heard the engines rev up, and I heard it roaring down the runway. But then it stopped all of a sudden. As soon as we finished unloading I ran down to see what was going on. I saw our DC7 sitting on the runway with its nose wheel yards away from a huge bomb crater. The pilot and a missionary were examining the hole. The missionary had heard the explosion and thought it was near the runway. He found the hole and also saw the DC7 starting its run toward him. He stood at the edge of the crater, facing the plane, and waved his arms frantically with a flashlight in each hand. The pilot told me that the flashlights were very faint from his perspective in the cockpit, but he could tell that there was something on the runway, so he throttled back and stood up on his brakes. With the plane roaring at him, the missionary never budged.

The plane maneuvered around the crater and took off. There was enough runway left for it to get airborne. From the bottom of the crater I pulled out a large piece of twisted, blackened metal, part of a tailfin from the bomb. It was still hot. I put it in my bag. I still have it, along with my drum and Baby Pancake.

I’m sorry to say that I don’t remember that missionary’s name, if I ever knew it. I only had a few contacts with him, but they were significant. I’m not even sure of his denomination, although it seems accurate in my memory to think of him as a Catholic. I will call him a generic “Father John.” After the plane took off Father John asked me to come with him, and we went to find the flight line officer. He was referred to as the “2IC,” or 2nd In Command, at Uli. We found him in the dark, and we all got in Father John’s station wagon. We drove to a house near the airfield. The residents of the house were asleep. The officer pounded on the door. “Wake up! Wake up! You’re holding up the Nation.” The man who emerged was in charge of airport maintenance. We drove him to his bulldozer, and he filled the crater. Tomorrow he would pave it, but tonight planes could land and take off on it.

The Biafrans had a Bofors antiaircraft gun. It had a distinctive, complicated sound, a low-throated pulse, “thoomp, thoomp,” with a kind of twang wrapped around it. One night it started firing and I got near a bunker but didn’t go in. When the bombs fell I could hear them tracking away from me, so I watched. They were phosphorous bombs and they made quite a light show, like fountains of fireflies in the night – umumuwari.

A bomb hit near a DC7 one night. The crew was standing outside. The copilot was severely injured and taken to the hospital. The plane was hit, but the pilot and flight engineer managed to get it airborne and headed for Sao Tome. The pilot also was injured with shrapnel in his legs. He told me later that he kneeled on the seat with his legs tucked under him to keep from passing out from the pain. Soon after takeoff one engine failed, and the second one on the same side gave out as they were landing. The oil filters in both engines were shredded. All the way back air was screaming through holes in the fuselage. The pilot spent a couple of months in the hospital on Sao Tome, and came out with a cane and a limp. I spent a couple of months working on that plane, but more about that later.

Some of the off-loading areas perpendicular to the runway were paved and others were covered with a steel mesh mat. A plane had gotten stuck in the mud off the runway and was vulnerable to attack the next day. By luck, it wasn’t. A few weeks later a plane arrived in Sao Tome with a load of those steel mesh mats. It was said that they had been diverted from Vietnam where they were to be used as helicopter landing pads. Whenever something odd like that happened, we all looked at an American missionary who was not affiliated with either WCC or Caritas. “He repeatedly said, “I do not work for the CIA! The only exercise we get around here is jumping at conclusions.” He was a small round man who looked like he could use some exercise.

Father John was tall, slender, and earnest. He never said much, but he listened attentively. After a bomb fell beyond the end of the runway one night, he came out of the dark and said, “Come with me.” Once again we rode off in his car. The bomb had fallen in a village compound, and there were casualties. Three members of the same family had run out of their house seeking cover when the bomb hit. A boy of about 20 years was dead. There was a ragged hole in his forehead and another near his navel. A boy of about 6 was hit in the leg. His leg was twisted at an odd angle. His eyes were open, but he made no sound. A young woman was hit in the arm. She was singing. The song was high, plaintive, haunting, and continuous. We put them in the station wagon and drove them to the hospital. When we left them the woman was still singing.

Uwa di egwu. The world is deep.

Previous WID Biafran Airlift Next WID Biafran Airlift People