Nonaka SECI Model

From Jsarmi

Contents |

Basics

The theory of organizational knowledge creation developed by Nonaka and his colleagues (Nonaka 1994; Nonaka et. al. 1994; Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995; Nonaka et. al. 2000; 2001a; Nonaka & Toyama 2003) originated in studies of information creation in innovating companies (Imai et. al. 1985; Nonaka 1988a, 1988b, 1990, 1991b, Nonaka & Yamanouchi 1989; Nonaka & Kenney 1991)

It appears to have undergone two phases of development.

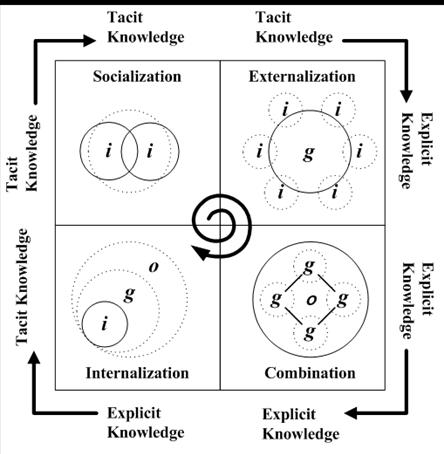

Initially a two dimensional theory of knowledge creation was proposed (Nonaka 1994: 16-17; Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 57-60). The first, or “epistemological”, dimension is the site of “social interaction” between tacit and explicit knowledge whereby knowledge is converted from one type to another, and new knowledge created (Nonaka et. al. 1994: 338; Nonaka 1994: 15). Four modes of knowledge conversion were identified:

- Tacit to tacit: Socialization.

- Tacit to Explicit: Externalization

- Explicit to Explicit: Combination

- Explicit to Tacit: Internalization.

After Internalization the process continues at a new ‘level’, hence the metaphor of a “spiral” of knowledge creation (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 71-2, 89) often referred to as the SECI model

Socialization

The SECI model claims that knowledge conversion begins with the tacit acquisition of tacit knowledge by people who do not have it from people who do, a process Nonaka and his colleagues named socialization. They give three examples of this process ( Nonaka 1991b: 98-9; Nonaka 1994: 19; Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 62-4; Nonaka et. al. 2001b: 17) of which the best documented study concerns the development of the automatic bread-making machine showing “how a tacit technical skill was socialized” (Nonaka 1991b: 98-9; Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 63-4, 100-109).

Externalization

Externalization, the next step in the knowledge conversion process, involves converting tacit into explicit knowledge, and holds the key to knowledge creation as new concepts are formed here (Nonaka 1994: 24; Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 66). Several cases of new product development are offered as examples of this process. The best documented case describes how managers set up a young team charged with producing a new car that was inexpensive but not cheap (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995:11-13, 69-70, 76-8, 86-7). When novelty proved difficult to achieve a team leader stimulated their creativity with his idea of “Automobile Evolution”. Using this and other similarly incongruous phrases ideas about what a new car might look like were generated and subsequently developed into a formal proposal for a new car.

The bread-making case seems to provide a more convincing example. Thus we are told that one of the design team “was able to transfer her knowledge [of making bread] to the engineers by using the phrase “twisting stretch” to provide a rough image of kneading” (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 104). The team was able to use this metaphor to think about how to replicate the motion in a machine. Externalization is also exemplified here in that the team were able to put their newly acquired tacit knowledge into a form of words and ultimately machine specifications that enabled them to produce the desired effects. This appears very like the processes Collins (1974, 2001) described – people who could do something but were not able to fully describe how they could do it worked hard at developing a description when it became necessary, and when it was apparent that they could not describe what they did in such a way as to enable someone else to do the same thing.

Combination

The next step in the SECI model is combination – the process of “systematizing concepts into a knowledge system” (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 67), which happens when people synthesize different sources of explicit knowledge into, for example, a report (Nonaka 1991b:99), or “through ... meetings and telephone conversations” and exchange of documents (Nonaka 1994: 19; Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 67). We are also told that an MBA education is “one of the best examples” of combination (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 67), and that modern computer systems provide a “graphic example” (Nonaka 1994: 19). Finally, combination also involves the ‘embodiment’ of knowledge into products (Nonaka 1991b:99; Nonaka et. al. 1996: 207-8).

Combination thus apparently consists of three (or four) kinds of activities: using language (talking, listening, reading, writing) to produce a synthesis; some unspecified aspect of computer functioning; and the ‘embodiment’ of knowledge into material goods. In so far as formal education involves language activities it can be subsumed under the first category, but it could also be separated out as learning/teaching, and thus constitute a fourth category of ‘combination’ activities. It is impossible to take seriously their claim that higher education simply or even largely involves ‘exchange’ of explicit knowledge (Adler, 1995). More significantly, none of these examples were discussed or described in ways that revealed their common properties as examples of the ‘combination’ of explicit knowledge, and no descriptions of ‘combination’ processes were offered. What might be involved in ‘reordering explicit knowledge’?

Internalization

The final cell of the matrix is labelled internalization, described as “a process of embodying explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge”. It is “closely related” to “the traditional notion of learning”, and to “learning by doing” (Nonaka et. al. 1994: 340-41; Nonaka 1994: 19; Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 69) although somewhat confusingly they also say that internalization is ‘triggered’ by learning-by-doing (Nonaka et. al. 1996: 208). Individuals can also internalize experiences by creating and reading documents: “Documentation helps individuals internalize what they experienced ... documents [help] ... people ... experience the experiences of others indirectly” (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 69). ‘Documentation’ is an ambiguous word that can mean ‘writing’ or reading. Books by business leaders, for example, are seen as a useful way of sharing mental models (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 70). Finally, internalization also involves, or is achieved through, the dissemination of explicit knowledge throughout an organization (Nonaka 1991b: 99; Nonaka et. al. 2001b: 19). Their description of ‘internalization’ is thus also a little confusing since so many activities appear to be involved in this process.

Evolution

While knowledge conversion is a social process its effects in the “epistemological” dimension appear to be on the individual since the second (“ontological”) dimension depicts the passage from individual to inter-organizational knowledge via group and organizational levels (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 73). Through this process an individual’s knowledge is ‘amplified’ and ‘crystallized’ “as a part of the knowledge network of an organization” (Nonaka 1994: 17-18). This is the process of organizational knowledge creation and it too is described as a ‘spiral’. The SECI components reappear at this level although in a different order (Nonaka et. al. 1994: 342; Nonaka 1994: 17; Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995: 73, 89-90, 235- 6).

Recently the two dimensions have become three elements or levels (Nonaka et. al. 2000; 2001a; 2001b). The SECI processes remain a key element but “ba”, or shared context of knowledge creation, and “knowledge assets” have replaced the “ontological” dimension (Nonaka et. al. 2001b:16). Knowledge creation, a “self-transcending process by means of which one transcends the boundary of the old self into a new self” (Nonaka et. al. 2001b: 16) clearly, if somewhat mystically, indicates a strong individual and subjective focus (see also Nonaka & Toyama 2003). The focus of this paper is the “engine” of knowledge creation - the SECI processes - so other elements of their model will not be discussed. Although the theory was first fully described in 1994 (Nonaka 1994; see Nonaka 1991a for some key elements) it has attracted little systematic criticism. Adler (1995) argued that it suffered from too static a contrast between tacit and explicit knowledge which he felt was inadequate for a dynamic model of tacit-explicit knowledge inter-relatedness (Adler 1995: 110-111). He also noted that several of the SECI modes had been studied by other disciplines, something Nonaka appeared to have overlooked (Adler 1995: 111). Jorna (1998) reviewing The Knowledge-Creating Company (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995) argued that since the four phases of ‘knowledge conversion’ concern a change of signs from one form to another a semiotic framework for dealing with signs is required, but is absent. He also noted the omission of many important philosophers, of learning theory, of earlier discussion of tacit and declarative knowledge, and the misreading of important organizational writers.

Criticisms

Several criticisms bot at the theoretical and empirical level have been published about Nonaka's model.

Complexity

Engeström noted Nonaka and Takeuchi’s accounts suggest teams took as given the problem to be worked on. His research, however, led him to conclude that formulating, analyzing and systematically locating the problem are key innovation processes (Engeström, 1999: 380, 388-90). Others have pointed to important contingent factors to the SECI processes: Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal (2001) show that each of the SECI modes is dependent on the presence of appropriate task characteristics while Poell and van der Krogt (2003), treating the modes as forms of learning, also report that work type influences how workers learn.

Lack of Empirical Evidence

The argument proposed by Gourlay (2003) and expanded in Bourlay & Nurse (2005) is that the evidence for the processes described by Nonaka is weak or non-existent which thus calls into question the SECI model itself. Since this remains at the heart of the overall theory, flaws in the SECI model will also affect the wider theory.

Gourlay, S. N. and Nurse, A. (2005) Flaws in the “Engine” of Knowledge Creation: A Critique of Nonaka’s SECI Model, Chapter 13 in Challenges and Issues in Knowledge Management, Buono, A. F., and Poulfelt, F. (eds) Research in Management Consulting Series, Volume 5, Greenwich, Connecticut: Information Age Publishing, pp. 293-315 (ISBN 1593114192). http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/sngourlay/PDFs/Chap%2013%20GourlayNurse.pdf

Gourlay, S. N. 2003, The SECI model of knowledge creation: some empirical shortcomings, in F. McGrath, and Remenyi, D., (eds), Fourth European Conference on Knowledge Management, Oxford, 18-19 September, pp. 377-385 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/sngourlay/PDFs/Gourlay%202004%20SECI.pdf

Bereiter's Folk Theory

Recently Bereiter (2002) has identified four important shortcomings in Nonaka’s approach. First, echoing Stacey (2001), he argues that Nonaka’s theory cannot explain how minds produce (or fail to produce) ideas. Second, it overlooks the important question of understanding—in order to learn by doing, one has to know what to observe. Third, while the theory recognizes knowledge abstracted from context, it says little about how it can be managed. Finally, the view that knowledge originates in individual minds prevents Nonaka from conceptualizing knowledge that arises from collective actions, for example, as a product of teamwork. Overall, Bereiter argues that the theory is rooted in a folk epistemology that regards individual minds as full of unformed knowledge that must be projected into an external world, an approach that hinders any attempt to provide a theory of knowledge creation. As such, he suggests that Nonaka’s theory fails both as a theory and as a practical tool for business.

See Also

http://cyberartsweb.org/cpace/////////cpace/ht/thonglipfei/nonaka_seci.html

http://www.12manage.com/methods_nonaka_seci.html

References

Adler, P.S. (1995). ‘Comment on I. Nonaka. Managing innovation as an organizational knowledge creation process’. In Allouche, J. and Pogorel, G. (Eds), Technology management and corporate strategies: a tricontinental perspective. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp 110-124.

Barfield, W.T. (n.d. [Preface dated 1947]). “Manna”. A comprehensive treatise on bread manufacture. 2nd ed. London: Maclaren & Sons Ltd. Becerra-Fernandez, I. and Sabherwal, R. (2001). ‘Organizational knowledge management: a contingency perspective’. Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol 18, No.1, pp 23- 55. Brent, D. (1992) Reading as rhetorical invention: knowledge, persuasion and the writing of research-based writing. Urbana, Ill.: National Council of Teachers of English. Cherry, C. (1966). On human communication. A review, a survey and a criticism. 2nd edn.Cambridge MA, and London: MIT Press. Collins, H.M. (1974). ‘The TEA set: tacit knowledge and scientific networks’. Science Studies, Vol 4, pp 165-86. Collins, H.M. (2001). ‘Tacit knowledge, trust, and the Q of sapphire’. Social studies of science, Vol 31, No.1, pp 71-85. Engeström, Y. (1999). ‘Innovative learning in work teams: analyzing cycles of knowledge 8 creation in practice’. In Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R. and Punamäki, R.-L., (Eds.), (1999). Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 377-406. Garavelli, A. C., Gorgoglione, M., Scozzi, B. (2002) ‘Managing knowledge transfer by knowledge technologies’, Technovation, Vol 22, pp 269-279. Goodman, K. S. (1996). Ken Goodman on reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Gourlay, S. N. (2001). ‘Getting from A to B: on the question of knowledge transfer’. European Group for Organizational Studies, 17th Colloquium 5-7 July 2001 Lyon, France. Imai, K., Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1985). ‘Managing the new product development process: how Japanese companies learn and unlearn’. In Clark, K.B., Hayes, R.H. and Lorenz, C. (Eds), The uneasy alliance. Managing the productivity-technology dilemma. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, pp 337-375. Jorna, R. (1998). ‘Managing knowledge’. Semiotic Review of Books, Vol 9, No.2, http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/epc/srb/srb/managingknow.html (accessed 17 Sept 2000). McAdam, R. and McCreedy, S. (1999). ‘A critical review of knowledge management models’. The Learning Organization, Vol 6, No.3, pp 91-100. Nonaka, I. and Kenney, M. (1991). ‘Towards a new theory of innovation management: a case study comparing Canon, Inc. and Apple Computer, Inc.’. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, Vol 8, No.1, pp 67-83. Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Nonaka, I., and Toyama, R. (2003). ‘The knowledge-creating theory revisited: knowledge creation as a synthesizing process’. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, Vol 1, pp 2-10. Nonaka, I. and Yamanouchi, T. (1989). ‘Managing innovation as a self-renewing process’. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol 4, pp 299-315. Nonaka, I. (1988a). ‘Creating order out of chaos: self-renewal in Japanese firms’. California Management Review, Vol 15, No.3, pp 57-73. Nonaka, I. (1988b). ‘Toward middle-up-down management: accelerating information creation. Sloan Management Review, Vol 29, No.3, pp 9-18. Nonaka, I. (1990). ‘Redundant, overlapping organization: a Japanese approach to managing the innovation process’. California Management Review, Vol 32, No.3, pp 27-38. Nonaka, I. (1991a). ‘The knowledge-creating company’. Harvard Business Review, November-December, pp 96-104. Nonaka, I. (1991b). ‘Managing the firm as an information creation process ‘. In Meindl, J.R., Cardy, R.L. and Puffer, S.M. (Eds), Advances in information processing in organizations. Greenwich, Conn., London: JAI Press Inc, pp 239-275. Nonaka, I. (1994). ‘A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation’. Organization Science, 5, 1, pp 14-37. Nonaka, I., Byosiere, P., Borucki, C.C. and Konno, N. (1994). ‘Organizational Knowledge Creation Theory: a first comprehensive test’. International Business Review, 3, 4, pp 337- 351. Nonaka, I., Umemoto, K. and Senoo, D. (1996). ‘From information processing to knowledge creation: a paradigm shift in business management’. Technology in Society, Vol 18, No.2, 203-218. Nonaka, I., Toyama, R. and Konno, N. (2000). ‘SECI, Ba, and leadership: a unified model of dynamic knowledge creation’. Long Range Planning, 33, pp 5-34. Nonaka, I., Toyama, R. and Byosière, P. (2001a). ‘A theory of organizational knowledge creation: understanding the dynamic process of creating knowledge’. In Dierkes, M., Antel, A.B., Child, J. and Nonaka, I. (Eds), Handbook of organizational learning and knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp 491-517. Nonaka, I., Konno, N. and Toyama, R. (2001b). ‘Emergence of “Ba”. A conceptual framework for the continuous and self-transcending process of knowledge creation’. In Nonaka, I. and Nishigushi, T. (Eds), Knowledge Emergence. Social, technical and evolutionary dimensions of knowledge creation. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, pp 3-29. Poell, R.F. and van der Krogt, F.J. (2003). ‘Learning strategies of workers in the knowledgecreating company’. Human Resource Development International 6, 3 (forthcoming). Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Polanyi, M. (1969). ‘Knowing and Being’. In Grene, M. (ed.), Knowing and being. Essays. London: Rutledge & Kegan Paul. Reinhart, P. (2001). The bread baker’s apprentice. Berkeley, Toronto: Ten Speed Press. Rosenblatt, M. (1994). The reader, the text, the poem. The transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale & Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press. Rosenblatt, M. (1998). ‘Readers, texts, authors’, Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society. XXXIV, 4, pp 885-921. Smith, F. (1994). Understanding reading. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Tsoukas, H. (2003). ‘Do we really understand tacit knowledge?’. In Easterby-Smith, M. and Lyles, M.A. (Eds), The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management. Malden, MA; Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp 410-427.