Central America

From Roach Busters

| Provincias Unidas del Centro de América United Provinces of the Center of America | |

| | |

|

|

| Flag | Coat of arms |

| | |

| Motto "Dios, Unión y Libertad" (Spanish) "God, Union and Liberty" | |

| | |

| Anthem La Granadera | |

| | |

| |

| | |

| Capital Largest city | San Salvador 13°40′N, 89°10′W Guatemala City |

| | |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| | |

| Demonym | Central American |

| | |

| Government - President - Vice-President | Federal republic Óscar Arias Rafael Espada |

| | |

| State religion | Roman Catholic Church |

| | |

| Establishment - Independence from Spain - Independence from Mexico - Constitution adopted | September 15, 1821 July 1, 1823 December 17, 1823 |

| | |

| Area - Total - Water (%) | 423,016 km² 163,362 sq mi 2.52 |

| | |

| Population - 2008 estimate - Density | 37,689,696 89/km² 231/sq mi |

| | |

| GDP (PPP) - Total - Per capita | 2007 estimate $547 billion $14,500 |

| | |

| GDP (nominal) - Total - Per capita | 2007 estimate $490 billion $13,000 |

| | |

| Gini (2006) | |

| | |

| HDI (2005) | |

| | |

| Currency | Central American real (CAR)

|

| | |

| Time zone - Summer (DST) | CST (UTC -6) not observed (UTC -6) |

| | |

| Internet TLD | .up |

| | |

| Calling code | +500 |

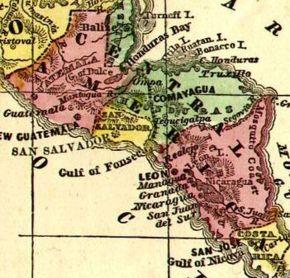

The United Provinces of the Center of America (Spanish: Provincias Unidas del Centro de América), commonly called Central America (Spanish: Centroamérica or América Central), is an upper-middle income nation in Central America. Bordering Mexico to the north, Belize to the northeast, and the Confederate States of Latin America to the south, it is one of the oldest republics in the Western Hemisphere. Formed by the union of Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, the nation will celebrate its bicentennial in 2023.

A geographically and culturally diverse nation abundant in resources, flora, and fauna, the United Provinces of Central America enjoys some of the greatest biodiversity in the world - bringing it to the attention of not only scientists, but also tourists, who flock to the country by the millions every year, earning the country much revenue. Also of note is the country's extensive, sometimes tumultuous, geographic activity; volcanic eruptions and earthquakes occur from time to time, with varying severity, from minor tremors to cataclysmic disasters taking thousands of lives (notable examples being the 1931 and 1972 Managua earthquakes).

An intensely socially conservative nation, it is the only country in the world where abortion is illegal without exception - even when the mother's life is in danger. Divorce and homosexuality remain social taboos, and the status of women leaves much to be desired. Though religious freedom is protected by law and the majority of Central Americans are tolerant of other faiths, the Roman Catholic Church remains the official religion, and, as can be surmised, wields a considerable amount of influence.

Though much social, political, and economic progress has been made in the past few decades, especially since the early 1980s, corruption remains a cause of concern and income and land distribution is among the most inequal in the world.

Contents |

History

Pre-colonial history

In pre-Columbian times, most of modern Central America was part of the Mesoamerican civilization. The Native American societies of Mesoamerica occupied the land ranging from central Mexico in the north to Costa Rica in the south. Most notable among these were the Maya, who had built numerous cities throughout the region, and the Aztecs, who created a vast empire. The pre-Columbian cultures of Panama traded with both Mesoamerica and South America, and can be considered transitional between those two cultural areas.

Colonization

Following Christopher Columbus's discovery of the Americas for Spain, the Spanish sent numerous expeditions to the region, and they began their conquest of Maya lands in the 1520s. In 1540, Spain established the Captaincy General of Guatemala, which extended from southern Mexico to Costa Rica, and thus encompassed most of what is currently known as Central America, with the exception of British Honduras (present-day Belize). This lasted nearly three centuries, until a rebellion (which followed closely on the heels of the Mexican War of Independence) in 1821.

Independence

In 1821 a congress of Central American criollos declared their independence from Spain, effective on 15 September of that year. That date is still marked as the independence day by most Central American nations. The Spanish Captain General, Gabino Gaínza, sympathized with the rebels and it was decided that he should stay on as interim leader until a new government could be formed. Independence was short-lived, for the conservative leaders in Guatemala welcomed annexation by the Mexican Empire of Agustín de Iturbide on 5 January 1822. Central American liberals objected to this, but an army from Mexico under General Vicente Filisola occupied Guatemala City and quelled dissent.

When Mexico became a republic the following year, it acknowledged Central America's right to determine its own destiny. On 1 July 1823, the congress of Central America declared absolute independence from Spain, Mexico, and any other foreign nation, and a republican system of government was established.

Early republic

In 1823 the nation of Central America was formed. It was intended to be a federal republic modeled after the United States of America. The Central American nation consisted of the states of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica.

Central American liberals had high hopes for the United Provinces, which they believed would evolve into a modern, democratic nation, enriched by trade crossing through it between the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. These aspirations are reflected in the emblems of the federal republic: The flag shows a white band between two blue stripes, representing the land between two oceans. The coat of arms shows five mountains (one for each state) between two oceans, surmounted by a Phrygian cap, the emblem of the French Revolution.

In the late 1830s, the nation nearly dissolved as a result of civil war, which directly resulted from Honduras's attempt to secede on November 5, 1838. A brief but economically disastrous war followed, which ended in 1840 with Honduras's re-integration into the Union.

The remainder of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th were characterized by alternating periods of spectacular economic growth and economic malaise, and general peace but severe political instability; most governments were both notoriously corrupt and short-lived. Two parties — the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party — dominated the political arena. The difference between the two was negligible. Both were staunchly conservative with strong ties to the Roman Catholic Church, and both represented the tiny but extremely powerful oligarchy, which, while numerically small, controlled the vast majority of the country's wealth and owned most of the land. Patronage, nepotism, and political infighting were rife. In concert with developments in Europe, class consciousness and social tensions gradually began to build in Central America.

United States involvement (1909—1933)

The early 20th century was characterized by pervasive involvement in Central American politics by the United States. In 1909, the U.S. provided political support to conservative-led forces rebelling against then-President Zelaya. U.S. motives included differences over the proposed Central American Canal and Zelaya's attempts to regulate foreign access to Central American natural resources. On November 18, 1909, U.S. warships were sent to the area after 500 revolutionaries (including two Americans) were executed by order of Zelaya. The U.S. justified the intervention by claiming to protect U.S. lives and property. Zelaya resigned later that year.

In August 1912 the President of Central America, Manuel Estrada Cabrera (who had succeeded Zelaya), requested that the Secretary of War, General Luis Mena, resign for fear that he was leading an insurrection. Mena fled San Salvador with his brother, the Chief of Police of San Salvador, to start an insurrection. When the U.S. Legation asked President Díaz to ensure the safety of American citizens and property during the insurrection he replied that he could not and that "In consequence my Government desires that the Government of the United States guarantee with its forces security for the property of American Citizens in Central America and that it extend its protection to all the inhabitants of the Republic."

U.S. Marines occupied Central America from 1912 to 1933, except for a nine month period beginning in 1925. Estrada ruled the country until 1923. He brought stability to Central America, often at the price of dictatorial rule. He encouraged development of the nation's infrastructure of highways, railroads, and sea ports. The United Fruit Company became an important force in Central America during his presidency. Opposition to his regime slowly grew; by 1920, opposition was widespread. In 1923, he was removed from office by the army, which charged that he was "mentally incompetent." With Estrada's departure went the nation's political stability; between 1923 and 1937, the country had eight Presidents.

Following the evacuation of U.S. Marines, another violent conflict between Liberals and Conservatives took place in 1926, known as the Constitutionalist War, which resulted in a coalition government and the return of U.S. Marines.

From 1927 until 1933, Gen. Augusto C. Sandino led a sustained guerrilla war first against the Conservative regime and subsequently against the U.S. Marines, who withdrew upon the establishment of a new Liberal government. Sandino was the only Central American general to refuse to sign the el tratado del Espino Negro agreement and then headed up to the northern mountains of Las Segovias, where he fought the U.S. Marines for over five years. The revolt finally forced the United States to compromise and leave the country. When the Americans left in 1933, they set up the Guardia Nacional (National Guard), a combined military and police force trained and equipped by the Americans. Anastasio Somoza García was put in charge of the Guardia Nacional. He was one of the three rulers of the country, the others being Sandino and the mostly figurehead President Juan Bautista Sacasa.

After the U.S. Marines withdrew from Nicaragua in January 1933, Sandino and the newly-elected Sacasa government reached an agreement by which he would cease his guerrilla activities in return for amnesty, a grant of land for an agricultural colony, and retention of an armed band of 100 men for a year. But a growing hostility between Sandino and Somoza led Somoza to order the assassination of Sandino. Fearing future armed opposition from Sandino, Somoza invited him to a meeting in Managua, where Sandino was assassinated on February 21, 1934 by the Guardia Nacional.

The Somoza era

In 1936, Somoza orchestrated a bloodless coup d'état, deposing Sacasa. A series of hand-picked puppets ruled for the remainder of the year; in December, Somoza was elected in his own right, and assumed office on New Year's Day, 1937. Somoza suspended the constitution, centralized and concentrated considerable power into his own hands, doled out important positions in the government and military to close relatives and friends, and accumulated a considerable fortune, primarily through investments in agricultural exports, but also by granting generous concessions to foreign (primarily American) companies to exploit gold, rubber and timber, for which he received 'executive levies' and 'presidential commissions.'

While opposition parties continued to exist (at least on paper), real power rested firmly in the hands of the Somoza family, and the two main parties, the Nationalist Liberal Party (Somoza's party) and the Conservative Party, had virtually indistinguishable platforms. The presidency rotated between Somoza and hand-picked candidates, but regardless of who held the presidency, the Somozas always wielded power behind the scenes, with the backing of the National Guard.

On a positive note, the country enjoyed a great degree of political stability and peace, and much economic progress was made. However, rampant corruption and an increasingly wide gap between the elite and the rural poor alienated many from Somoza.

In the international arena, Somoza aligned his country closely with the United States. Central America became the first country in Latin America to join the United States in formal declaration of World War II, and it was also a major supplier of materials to the U.S. war effort. Central America was also one of the original signatories to the United Nations Charter (and the first nation in the world to ratify the UN charter). With the advent of the Cold War, Somoza, well-known as a staunch anticommunist, readily received U.S. support. Central America gained a reputation as one of the most outspokenly pro-Western and anticommunist countries in the Third World.

In 1948, in the aftermath of a highly disputed election (which, naturally, Somoza won), José Figueres Ferrer led an armed uprising against the government. With more than 2,000 dead, the resulting 44-day civil war was the bloodiest event in Central American history during the twentieth-century. Afterwards, the new, victorious government junta, led by the opposition, abolished the National Guard (replacing it with an apolitical, professional military), sent Somoza into exile (where he ended up settling in Miami, Florida), and oversaw the drafting of a new constitution by a democratically-elected assembly. Most significantly, the country's draconian ballot access laws were relaxed, effectively ending the two-party duopoly that had endured since the 19th century. Several new parties sprung into being as a result, including the social democratic National Liberation Party (Partido Liberación Nacional), founded by Figueres.

Having enacted these reforms, the regime finally relinquished its power on November 8, 1949 to the new democratic government. After the coup d'état, Figueres became a national hero, winning the country's first democratic election under the new constitution in 1953.

Today, Somoza's legacy is a mixed one. His supporters characterize him as a "benevolent dictator," citing the progress Central America made on the economic front as well as the general stability that prevailed through his administration. However, his detractors are quick to point out that under Somoza, corruption reached endemic proportions, the country's illusory "democracy" was a façade, and dissent was not tolerated. Somoza himself was known as saying that he was personally in favor of democracy, but only when the country was "ready" for it. In a 1953 interview with the New York Times, he said, "I would like nothing better than to give [the Central Americans] the same kind of freedom as that of the United States...It is like what you do with a baby. First you give it milk by drops, then more and more, then a little piece of pig, and finally it can eat everything...You cannot give a bunch of five-year-olds guns...They will kill each other. You have to teach them how to use freedom, not to abuse it."

Somoza died of natural causes in Miami, Florida on September 29, 1956. He was 60 years old.

The 1950s: Central America on the upswing

The government of José Figueres Ferrer was the most progressive one Central America ever had. Women's suffrage was granted; the banking, telecommunications, and utilities sectors were nationalized; resources earmarked for education increased 250% between 1953 and 1958; a generous social security system and labor code were introduced; and ambitious public works programs were launched. Central America pursued a pragmatic, middle-of-the-road economic policy, combining a business-friendly environment with a progressive welfare state, in an effort to counterbalance both reactionary oligarchs and an increasingly militant left-wing grassroots movement. Figueres maintained the pro-American foreign policy initiated by his predecessors.

Figueres was immensely popular both at home and abroad for his reformism, pragmatism, and strenuous opposition to extremism on both ends of the political spectrum. While he came nowhere close to fulfilling all his goals (especially in the area of land reform), he left office with very high approval ratings.

1960s—1970s: Return of the Somozas, the specter of Cuba

Shortly before leaving office, Figueres granted former President Somoza a posthumous pardon, and permitted the Somoza family to return to Central America from exile. They did so, and to the surprise of many, Somoza's elder son, Luis Somoza Debayle, entered the presidential race in 1958 and won. He proved to be a great deal more moderate and lenient of opposition than his father, he was criticized for appointing a disproportionate number of family members and close friends to top government and military positions, and several companies owned by the Somoza family and its friends acquired monopolies and accumulated millions in illicit wealth. The escalating level of corruption effectively radicalized certain segments of the population — particularly left-leaning clergy, college students, and trade unions — and made them ripe for communist infiltration.

Central America earned the undying hatred of Cuba's Fidel Castro when, in 1960, the country provided basing and logistical support for the ill-fated Bay of Pigs operation. Castro retaliated in kind by covertly funneling weapons and money to anti-government groups. In 1962, a radical left-wing guerrilla organization, the Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional), named after the late revolutionary Augusto C. Sandino, was created, with the goal of overthrowing the government and establishing a Marxist-Leninist state aligned with the Soviet bloc. Beginning in 1964, a low-key insurgency began, with sporadic skirmishes between guerrillas and government forces taking place, mostly in the countryside.

In 1966, Luis's term came to an end, and he was succeeded by René Schick, widely viewed as a weak politician. Cynics lamented — not without justification — that the Somozas were the real "power behind the throne" during this time. Even so, Luis's death in 1966 effectively prevented him from exerting strong control over Schick, but Luis's younger brother, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, was soon appointed an unofficial advisor, and became a President in all but name. This did not escape the notice of the Central American people, and anti-government opposition began to build.

Somoza himself would assume the presidency in 1970, in an election widely boycotted by the opposition.

to be continued

Economy

to be added

Politics

Central America is a federal republic with a level of de-centralization surpassed only by Switzerland. Like Switzerland, it is highly democratic, and the Constitution guarantees a great deal of civil liberties. Unlike Switzerland, the Central American government remains dominated by a parochial elite, and corruption and patronage remain widespread. While the government generally honors the Constitution's commitments to personal freedoms, politics remains a game played with loaded dice, in which, regardless of the electoral outcome, the players remain largely the same. Even so, Central Americans are a public-spirited, civic-minded, highly politically active people, and elections are eagerly anticipated occasions and public debate is lively. The country's fairly high living standards, and the large degree of freedom people enjoy in their daily lives, causes most Central Americans to overlook the many inherent flaws in their political system.

Political parties

- National Liberation Party (Partido Liberación Nacional)

- Nationalist Liberal Party (Partido Liberal Nacionalista)

- Christian Democratic Party (Partido Demócrata Cristiano)

- Nationalist Republican Alliance (Alianza Republicana Nacionalista)

- Citizens' Action Party (Partido Acción Ciudadana)

- Libertarian Movement Party (Partido Movimiento Libertario)

- Constitutionalist Liberal Party (Partido Liberal Constitucionalista)

- Ecologist Green Party (Partido Verde Ecologista)

- Socialist Party (Partido Socialista)

Federal government

Legislature

The legislative branch of Central America is the unicameral Federal Congress (Congreso Federal), whose members are popularly elected on a numerical basis, renewable by halves each year. Its primary function is to adopt federal laws (i.e, draft bills). The Federal Congress convenes in the National Palace (Palacio Nacional).

The Senate

The Central American Senate (Senado) differs from most other senates in that it is not a legislative body. It takes no initiative in the formulation of laws, but instead simply approves or denies bills. It also functions as an advisory body to the executive branch and serves as a "moderator power." The membership of the Senate is popularly elected and renewable by thirds each year.

Executive

The head of state in Central America is the President (Presidente), who presides over the executive branch. Unlike the President of the United States, who is elected by the Electoral College, the President of Central America is popularly elected; like the President of the U.S., the Central American President's term is four years long. He is eligible for re-election, but his terms must be consecutive. For example, if the incumbent President loses the next election, he may not run again. A President is limited to a maximum of two terms. The President and the Vice-President (Vicepresidente) are elected on the same ticket. The President has very limited powers and cannot veto bills. His main duty is to enforce public order and direct the military of Central America. He also conducts foreign policy in consultation with the Senate, which also proposes lists for the appointment of federal officials. Finally, the President presides over the Senate, but cannot vote except in the event of a tie. The Vice-President mainly serves as a "spare wheel," for the President; in the event that the President dies, resigns, becomes incapacitated, is removed from office, or is otherwise unable to fulfill his duties, the Vice-President does so in his stead. The President's official residence is the Casa Presidencial (English: "Presidential House") in San Salvador. His annual salary is 175,000 reales.

Cabinet

- Minister of Agriculture and Animal Husbandry (Ministro de Agricultura y Ganadería): Rafael Ocón Mora

- Minister of Defense (Ministro de Defensa): Julio Salazar Ramirez

- Minister of Economy, Industry, and Commerce (Ministro de Economía, Industria y Comercio): Rómulo Martínez Hidalgo

- Minister of Foreign Relations (Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores): Roberto de Paula Hernández

- Minister of Finance and Public Credit (Ministro de Hacienda y Crédito Público): Tomás Caldera Guitierrez

- Minister of the Government (Ministro de la Gobernación): Rubén Urtecho Vegas

- Minister of Justice (Ministro de Justicia): Ramón García Guzmán

- Minister of Labor (Ministro del Trabajo): Leonardo Gallardo Ugarte

- Minister of Public Education (Ministro de Educación Pública): César López Sánchez

- Minister of Public Health (Ministro de Salud Pública): José Rafael Espada

- Minister of Public Works (Ministro de Obras Públicas): Amilcar Guerrero Cerezo

- President of the Central Bank ((Presidente del Banco Central)): Francisco Volio Uribe

- Permanent Representative to the United Nations (Representante Permanente ante las Naciones Unidas): Jorge Garnier Núñez

Judiciary

The Supreme Court of Justice (Suprema Corte de Justicia), the judiciary, differs from most other judicial bodies around the world in that its membership is popularly elected (renewable by thirds every two years). The Supreme Court of Justice functions as a court of last resort, hears cases against the President and other senior officials, and establishes juries and appellate courts. All citizens, without distinction, are subject to the same order of proceedings and trials; in other words, there are no special courts for the military and ecclesiastical jurisdictions.

State governments

The composition of state governments is largely similar to that of the federal government. Each state has a unicameral legislative body, known as Congress (Congreso); a Representative Council (Consejo Representativo), which sanctions or vetoes laws passed by Congress, essentially performing the same function as the Senate does at the federal level); an executive, known as the Chief (Jefe), assisted by a Second Chief (Segundo Jefe); and a judiciary (like its federal counterpart, known as the Supreme Court of Justice). Each of these is popularly elected in the same manner as their counterparts at the federal level, and fulfill the same duties. The Constitution stipulates that whatever powers are not explicitly granted to the federal government, nor denied by it to the states, are reserved for the state and local governments.

List of States

Political parties

For most of its history, the country's politics have revolved around two political parties, the Liberal Party (Partido Liberal) and the Conservative Party (Partido Conservador). Both parties are more groupings of members of the Federal Congress than ideologically based movements dependent on distinct electorates. No particular political philosophy distinguishes one group from another; however, while ideological differences between the two parties are rather negligible, the Liberals vaguely represent labor and social programs and the interests of artisans and workers, while the Conservatives vaguely represent certain business sectors and are more closely affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church.

In reality, members of both parties come from the same social groups: Plantation owners, bureaucrats, professionals, and businessmen. Though the differences between the parties are trivial, factional and personal rivalries among the two parties (and even within them) are intense, and make cooperation difficult. Both parties also tend to be dominated by wealthy politically-connected families: The Liberals by the Somoza family, and the Conservatives by the Figueres family. Patronage is rife within both parties, and contacts and favor rather than ability determine success in party circles.

While third parties are perfectly legal and do exist, the domination of most television stations, newspapers, and other media by the Somoza and Figueres families, coupled with draconian ballot access laws, effectively makes it impossible for other parties to come to power, except at the local and, very rarely, the state level.

More importantly, a constitutional provision, implemented in the 1970s, allows the Liberals and Conservatives to monopolize power. Following widespread riots after the disputed 1968 presidential election, a behind-the-scenes power-sharing compromise was reached. Whichever party won congressional elections would receive 60% of the seats, and the other party, regardless of how much lower its share of the vote was, would receive the remaining 40%. This "compromise" remains a contentious issue in Central America, and many are calling for its repeal, though it remains to be seen whether or not this will happen.

The Constitution proscribes the formation of Marxist political parties or organizations.