Brazil

From Roach Busters

| República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil Republic of the United States of Brazil | |

| | |

|

|

| Flag | Coat of arms |

| | |

| Motto "Ordem e Progresso" (Portuguese) "Order and Progress" | |

| | |

| Anthem Hino Nacional Brasileiro (National Anthem of Brazil) | |

| | |

| |

| | |

| Capital Largest city | Brasília São Paulo |

| | |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| | |

| Demonym | Brazilian |

| | |

| Government - President - Vice-President | Unitary presidential republic João de Oliveira Mendonça Afonso Branco |

| | |

| Independence - Declared - Recognized - Republic - Coup d'état | from Portugal September 7, 1822 August 29, 1825 November 15, 1889 March 31, 1964 |

| | |

| Area - Total - Water (%) | 8,514,877 km² 3,287,597 sq mi 0.65 |

| | |

| Population - 2008 estimate - 2007 census - Density | 186,757,608 183,987,291 22/km² 57/sq mi |

| | |

| GDP (PPP) - Total - Per capita | 2007 estimate $3.88 trillion $20,777 |

| | |

| GDP (nominal) - Total - Per capita | 2007 estimate $2.24 trillion $11,973 |

| | |

| Gini (2005) | |

| | |

| HDI (2005) | |

| | |

| Currency | Real (R$) (BRL)

|

| | |

| Time zone - Summer (DST) | BRT (UTC -2 to -4) BRST (UTC -2 to -3) |

| | |

| Internet TLD | .br |

| | |

| Calling code | +55 |

Brazil (Portuguese: Brasil), officially the Republic of the United States of Brazil (Portuguese: República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil) is a country in South America. With a population of over 185 million and an area of 8,514,877 km² (3,287,597 sq mi), it is one of the largest and most populous countries in the world. Bounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the east, Brazil has a coastline of over 7,491 kilometers (4,655 mi). It is bordered on the north by Venezuela, Suriname, Guyana and the overseas department of French Guiana; and on the northwest, west, southwest, and south by the Confederate States of Latin America. Numerous archipelagos are part of the Brazilian territory, such as Fernando de Noronha, Rocas Atoll, Saint Peter and Paul Rocks, and Trindade and Martim Vaz.

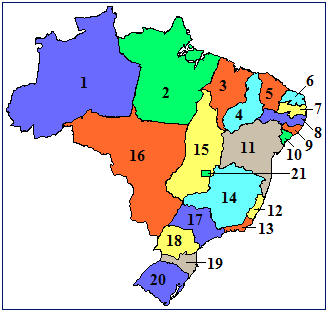

Brazil was a colony of Portugal from the landing of Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500 until its independence in 1822. Initially independent as the Empire of Brazil, the country has been a republic since 1889, although the bicameral legislature, now called Congress, dates back to 1824, when the first constitution was ratified. Its current constitution defines Brazil as a federal republic, but in practice the country is a unitary state in which the states enjoy little autonomy. Brazil comprises 21 States (including the Distrito Federal, or "Federal District") and 5,564 Municipalities.

Economic reforms have transformed Brazil into a great power. The country is a founding member of the League of Nations. A predominantly Roman Catholic, Portuguese-speaking, and multiethnic society, Brazil is also home to a diversity of wildlife, natural environments, and extensive natural resources in a variety of protected habitats.

Contents |

History

Origins

Within Brazil's current borders, most native tribes who were living in the land by the year 1500 are thought to have descended from the first wave of migrants from North Asia (Siberia), who are believed to have crossed the Bering Land Bridge at the end of the last Ice Age, around 9000 BC. At the time of European discovery, the territory of modern Brazil had as many as 2,000 nations and tribes, an estimated total population of nearly 3 million Amerindians. A somewhat dated linguistic survey found 188 living indigenous languages with 155,000 total speakers. On 18 January 2007, Fundação Nacional do Índio reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. With this addition, Brazil is now confirmed as having the largest number of uncontacted peoples in the world, even more than the island of New Guinea. When the Portuguese arrived in 1500, the Amerindians were mostly semi-nomadic tribes, living mainly on the coast and along the banks of major rivers.

Unlike Christopher Columbus who thought he had reached the East Indies, the Portuguese, most notably by Vasco da Gama, had already reached India via the Indian Ocean route when they reached Brazil. Nevertheless, the word índios ("Indians") was by then established to designate the peoples of the New World and stuck being used today in the Portuguese language, while the people of India are called indianos in order to distinguish the two peoples. Initially, the Europeans saw the natives as noble savages, and miscegenation of the population began right away. Tribal warfare, cannibalism, and the pursuit of brazilwood for its treasured red dye convinced the Portuguese that they should civilize the Amerindians.

Colonization

Initially Portugal had little interest in Brazil, mainly because of high profits gained through commerce with Indochina. After 1530, the Portuguese Crown devised the Hereditary Captaincies system to effectively occupy its new colony, and later took direct control of the failed captaincies. Although temporary trading posts were established earlier to collect brazilwood, used as a dye, with permanent settlement came the establishment of the sugar cane industry and its intensive labor. Several early settlements were founded across the coast, among them the colonial capital, Salvador, established in 1549 at the Bay of All Saints in the north, and the city of Rio de Janeiro on March 1567, in the south. The Portuguese colonists adopted an economy based on the production of agricultural goods that were exported to Europe. Sugar became by far the most important Brazilian colonial product until the early 18th century. Even though Brazilian sugar was reputed as being of high quality, the industry faced a crisis during the 17th and 18th centuries when the Dutch and the French started producing sugar in the Antilles, located much closer to Europe, causing sugar prices to fall.

During the 18th century, private explorers who called themselves the Bandeirantes found gold and diamond deposits in the state of Minas Gerais. The exploration of these mines were mostly used to finance the Portuguese Royal Court's expenditure with both the preservation of its Global Empire and the support of its luxury lifestyle at mainland. The way in which such deposits were exploited by the Portuguese Crown and the powerful local elites, however, burdened colonial Brazil with excessive taxes. Some popular movements supporting independence came about against the taxes established by the colonial government, such as the Tiradentes in 1789, but the secessionist movements were often dismissed by the authorities of the ruling colonial regime. Gold production declined towards the end of the 18th century, starting a period of relative stagnation of the Brazilian hinterland. Both Amerindian and African slaves' man power were largely used in Brazil's colonial economy.

In contrast to the neighboring Spanish possessions in South America, the Portuguese colony of Brazil kept its territorial, political and linguistic integrity due to the action of the Portuguese administrative effort. Although the colony was threatened by other nations across the Portuguese rule era, in particular by Dutch and French powers, the authorities and the people ultimately managed to protect its borders from foreign attacks. Portugal even had to send bullion to Brazil, a spectacular reversal of the colonial trend, in order to protect the integrity of the colony.

Empire

In 1808, the Portuguese court, fleeing from Napoleon’s troops who had invaded Portugal, established themselves in the city of Rio de Janeiro, which thus became the seat of government of Portugal and the entire Portuguese Empire, even though being located outside of Europe. Rio de Janeiro was the capital of the Portuguese empire from 1808 to 1815. After then the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves (1815-1825) was created with Lisbon as its capital. After João VI returned to Portugal in 1821, his heir-apparent Pedro became regent of the Kingdom of Brazil, within the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Following a series of political incidents and disputes, Brazil achieved its independence from Portugal on September 7, 1822. On October 12, 1822, Dom Pedro became the first Emperor of Brazil, being crowned on December 1, 1822. Portugal would recognize Brazil as an independent country in 1825.

In 1824, Pedro closed the Constituent Assembly, stating that the body was "endangering liberty". Pedro then produced a constitution modeled on that of Portugal (1822) and France (1814). It specified indirect elections and created the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government; however, it also added a fourth branch, the "moderating power", to be held by the Emperor. Pedro's government was considered economically and administratively inefficient. Political pressures eventually made the Emperor step down on April 7, 1831. He returned to Portugal leaving behind his five-year-old son Pedro II. Until Pedro II reached maturity, Brazil was governed by regents from 1831 to 1840. The regency period was turbulent and marked by numerous local revolts including the Male Revolt, the largest urban slave rebellion in the Americas, which took place in Bahia in 1835.

On July 23, 1840, Pedro II was crowned Emperor. His government was marked by a substantial rise in coffee exports, the War of the Triple Alliance, and the end of slave trade from Africa in 1865, although slavery in Brazilian territory would only be abolished in 1888. Brazil stopped trading slaves from Africa in 1850, with the Eusébio de Queirós law, and abandoned slavery altogether in 1888, thus becoming the last country of the Americas to ban slavery. When slavery was finally abolished, a large influx of European immigrants took place. By the 1870s, the Emperor's control of domestic politics had started to deteriorate in face of crises with the Catholic Church, the Army and the slaveholders. The Republican movement slowly gained strength. In the end, the empire fell due to a military coup d'etat and because the dominant classes no longer needed it to protect their interests and deeply resented the abolition of slavery. Indeed, imperial centralization ran counter to their desire for local autonomy. By 1889 Pedro II had stepped down and the Republican system had been adopted to Brazil.

Early republic

Pedro II was deposed on November 15, 1889 by a Republican military coup led by general Deodoro da Fonseca, who became the country’s first de facto president through military ascension. The country’s name became the Republic of the United States of Brazil. From 1889 to 1930, the dominant states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais alternated control of the presidency. A military junta took control in 1930. Getúlio Vargas took office soon after, and would remain as dictatorial ruler (with a brief democratic period in between), until 1945. He was re-elected in 1951 and stayed in office until his suicide in 1954. After 1930, successive governments continued industrial and agricultural growth and the development of the vast interior of Brazil. Juscelino Kubitschek's office years (1956-1961) were marked by the political campaign motto of plunging 50 anos em 5 (English: "Fifty years of development in five").

Military junta

The military once again seized power in Brazil when it launched a successful coup d'état on March 31, 1964, toppling the left-leaning government of President João Goulart. Goulart's reforms, contemporaneously interpreted as socialist in a world increasingly polarized by the Cold War, went against the interests of the military and the right-wing of the civilian government. The coup was tacitly supported by the Johnson Administration in the United States, due to America's fear of the perceived growing communist influence in Brazil. The extent of the United States' involvement in the coup remains unknown to this day, but the support it did provide remains a source of contention for Brazilian pro-democracy activists to this day.

Right after the coup, the army did not find any civilian politician acceptable to all the factions that supported the ouster of João Goulart. On April 15, 1964, fifteen days after the coup, the army chief of staff, Marshal Humberto de Alencar Castello Branco became the appointed president, with the intention of overseeing a reform of the political-economic system. He refused to remain in power beyond the remainder of Goulart's term or to institutionalize the military in power. However, competing demands radicalized the situation; military hard-liners wanted a complete purge of left-wing and populist influences, while civilian politicians obstructed Castello Branco's reforms. The latter accused him of hard-line actions to achieve his objectives, and the former criticized him for not being hard enough. To satisfy the military hard-liners, he recessed and purged Congress, removed objectionable state governors, and decreed the expansion of the president's (and by extension, the military's) arbitrary powers at the expense of the legislative and judiciary branches. His gamble succeeded in giving him the latitude to repress the populist left but provided his successors with a legal basis for authoritarian rule.

Castello Branco in his own right tried to maintain a degree of democracy. His economic reforms were credited as paving the way for a Brazilian economic "miracle" of the next decade, and his restructuring of the party system that had existed since 1945 shaped the bipartisan system of government-opposition relations for the next two decades. Through extra-constitutional decrees dubbed "Institutional Acts" (Portuguese: Ato Institucional, or "AI"), Castelo Branco both gave the executive the unchecked ability to change the constitution and remove anyone in office ("AI-1") as well as to have the presidency elected indirectly through a bipartisan system of a government-backed National Renewal Alliance Party (ARENA) and an opposition Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB) party ("AI-2"). In effect, anyone who opposed the government politically was removed from office, and the parties were known as either the "Yes" party in the case of ARENA, and the "Yes, sir" party in the case of the MDB.

As in earlier regime changes, the armed forces' officer corps was divided between those who believed that they should confine themselves to their professional duties, and the hard-liners who regarded politicians as willing to turn Brazil to communism. The victory of the hard-liners dragged Brazil into what political scientist Juan J. Linz called "an authoritarian situation". Indeed, the hard-liners in the Brazilian military pressured the government into promulgating the Fifth Institutional Act on December 13, 1968. This act gave the president dictatorial powers, dissolved Congress and state legislatures, suspended the constitution, and imposed censorship.

The military sought to expand Brazil's influence in the world by pursuing a state-led industrial policy and an independent foreign policy. Massive investments in infrastructure - highways, telecommunications, hydroelectric dams, mineral extraction, factories, and atomic energy - funded by heavy borrowing, created a temporary inflationary boom, and from 1968 to 1974, the annual GDP growth rate was 12%. The construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway through the northern rain forests and the Itaipu hydroelectric dam (the world's largest) on the Rio Paraná, provided thousands of unemployed Brazilians with work. A growing sense of optimism temporarily muted public discontent (although state repression also played a hand), and the government, gambling that the prosperity would be permanent, continued to borrow heavily and spend beyond its means. All this came to a crashing halt in 1975, when a combination of skyrocketing oil prices, a terrible coffee frost (which nearly halved Brazil's coffee output), and other factors contributed to a dramatic fall in GDP. In desperation, the regime began rapidly printing money in an attempt to pay off the country's enormous debt, but the ensuing inflation (which reached nearly 1,000% by 1979) brought about a near-total collapse of the economy, forcing Brazil to accept loans from the IMF and World Bank - burdening it with still further debt.

By 1980, the situation in Brazil constituted the worst crisis in the country's history. Its economy was a shambles; crime rates soared; and riots, strikes, and demonstrations afflicted every major city. Most foreign analysts predicted that the government would collapse, taking the whole country with it.

Publicly acknowledging that its economic policies had been a disaster, the government brought in foreign economists to help them implement a new policy. These young, clean-cut, highly sophisticated technocrats, renowned for their irrepressible confidence (they were perhaps the only people who could talk frankly to the government and criticize it), drafted an economic plan which called for privatization of state-owned industries, stabilization of inflation, and trade liberalization. After much cajoling, the "whiz kids," as the technocrats came to be known, won over the government, which threw in its lot with them and took the plunge.

Within three years, inflation had been brought under control and foreign investors began returning to the country. The economy rapidly recovered. From 1980–1985, GDP growth averaged more than 10%. However, the government's decision to keep fixed exchange rates resulted in a serious balance-of-trade problem that soon brought a deep recession. In 1986, GDP fell by 13 per cent, industrial production plunged by 27 per cent, and unemployment shot up to 20 per cent. Real economic output declined by 19% that year, and again the following year. The government responded by floating the exchange rate, drastically cutting spending, lowering taxes and tariffs, and tightening the money supply. As a result, the recession was over by 1988.

Since that time, Brazil's economy has continued to experience spectacular growth, with only a few intermittent hiccups. Almost every industry has been privatized (although major defense companies like Engesa and Embraer remain state-owned for "strategic reasons"), tariffs were continually cut until being abolished altogether by 1998, wage and price controls were eliminated, and the government has maintained a balanced budget. Unemployment and inflation are at a historic low, and the country's economy is now among the world's largest. However, inequality in income and land distribution has grown explosively and the country's high crime rate continues to climb. Demonstrations by university students and pro-democratic activists began to occur with growing frequency.

As of 2008, the Brazilian economy and government are as stable as ever, while the stability of society remains tenuous and precarious. Governmental repression has failed to quell anti-government activism, which is again on the rise; the crime rate remains high; and beneath the surface of prosperity, class tensions simmer. Brazil has accomplished much and made many advances, but still faces various problems and challenges which continue to thwart its ambition to become a superpower. How Brazil weathers these challenges, and what prospects its future holds, remains to be seen.

States of Brazil

- Amazonas

- Pará

- Maranhão

- Piauí

- Ceará

- Rio Grande do Norte

- Paraíba

- Pernambuco

- Alagoas

- Sergipe

- Bahia

- Espírito Santo

- Rio de Janeiro

- Minas Gerais

- Goiás

- Mato Grosso

- São Paulo

- Paraná

- Santa Catarina

- Rio Grande do Sul

- Distrito Federal

List of Brazilian states

| State | Abbreviation | Capital | Area | Population (2005) | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alagaos | AL | Maceió | 27,767.7 km² | 3,015,912 | 108.61 |

| Amazonas | AM | Manaus | 1,947,626.1 km² | 4,279,690 | 2.2 |

| Bahia | BA | Salvador | 564,692.7 km² | 13,815,334 | 24.46 |

| Ceará | CE | Fortazela | 148,825.6 km² | 8,097,276 | 54.40 |

| Distrito Federal | DF | Brasília | 5,802 km² | 2,383,784 | 410.9 |

| Espírito Santo | ES | Vitória | 46,077.5 km² | 3,408,365 | 73.97 |

| Goiás | GO | Goiânia | 623,529.7 km² | 9,258,753 | 14.85 |

| Maranhão | MA | São Luís | 331,983.3 km² | 6,103,327 | 18.38 |

| Mato Grosso | MT | Cuiabá | 1,498,059.1 km² | 6,602,336 | 4.4 |

| Minas Gerais | MG | Belo Horizonte | 586,528.3 km² | 19,237,450 | 32.79 |

| Pará | PA | Belém | 1,390,504.1 km² | 7,565,173 | 5.44 |

| Paraíba | PB | João Pessoa | 56,439.8 km² | 3,595,886 | 63.71 |

| Paraná | PR | Curitiba | 199,314.9 km² | 10,261,856 | 51.48 |

| Pernambuco | PE | Recife | 98,311.6 km² | 8,413,593 | 85.58 |

| Piauí | PI | Teresina | 251,529.2 km² | 3,006,885 | 11.95 |

| Rio de Janeiro | RJ | Rio de Janeiro | 43,696.1km² | 15,383,407 | 352.05 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | RN | Natal | 52,796.8 km² | 3,003,087 | 56.88 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | RS | Porto Alegre | 281,748.5 km² | 10,845,087 | 38.49 |

| Santa Catarina | SC | Florianópolis | 95,346.2 km² | 5,866,568 | 61.53 |

| São Paulo | SP | São Paulo | 248,209.4 km² | 40,442,795 | 162.93 |

| Sergipe | SE | Aracaju | 21,910.3 km² | 1,967,761 | 89.81 |

Politics

Presidency

The President of Brazil is both the head of state and head of government of the Republic of the United States of Brazil. The presidential system was established in 1889, upon the proclamation of the republic in a military coup d’état against the Emperor Pedro II. The President is indirectly elected by the Electoral College (Colégio Eleitoral) to a five-year term.

As a presidential republic, Brazil grants significant powers to the President. He effectively controls the government, represents the country abroad, and appoints the Cabinet and judges for the Supreme Federal Tribunal. The president is also the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.

Presidents in Brazil also have significant lawmaking powers, exercised either by proposing laws to the National Congress, or by using the instrument of the Decretos-Lei, a decree that becomes binding after 30 days if the Congress "does not have the time" to vote on it.

The Constitution determines that the President shall have the exclusive power to:

- Appoint and dismiss the Ministers of State;

- Exercise, with the assistance of the Ministers of State, the higher management of the federal administration;

- Start the legislative procedure, in the manner and in the cases set forth in the Constitution;

- Sanction, promulgate and order the publication of laws, as well as to issue decrees and regulations for the true enforcement thereof;

- Veto bills, wholly or in part;

- Provide, by means of decree, on organization and structure of federal administration, in the cases where there is neither increase of expenses nor creation or extinction of public agencies; and extinction of offices or positions, when not held;

- Maintain relations with foreign States and to accredit their diplomatic representatives;

- Conclude international treaties, conventions, and acts;

- Decree the state of defense and the state of siege;

- Decree and enforce federal intervention;

- Upon the opening of the legislative session, send a government message and plan to the National Congress, describing the state of the nation and requesting the actions he deems necessary;

- Grant pardons and reduce sentences, after hearing the entities instituted by law, if necessary;

- Exercise the supreme command of the Armed Forces, appoint the commanders of Navy, Army and Air Force, to promote general officers and to appoint them to the offices held exclusively by them;

- Appoint the Justices of the Supreme Federal Court and those of the superior courts, the Governors of the territories, the Attorney-General of the Republic, the President and the Directors of the Central Bank and other civil servants;

- Appoint the Justices of the Federal Court of Accounts;

- Appoint judges in the events established by the Constitution and the Advocate-General of the Union;

- Appoint members of the Council of the Republic;

- Call and preside over the Council of the Republic and the National Defense Council;

- Declare war, in the event of foreign aggression, and decree full or partial national mobilization;

- Award decorations and honorary distinctions;

- Permit, in the cases set forth by supplementary law, foreign forces to pass through the national territory, or to remain temporarily therein;

- Submit to the National Congress the pluriannual plan, the bill of budgetary directives and the budget proposals set forth in the Constitution;

- Render, each year, accounts to the National Congress concerning the previous fiscal year, within sixty days of the opening of the legislative session;

- Fill and abolish federal government positions, as set forth by law;

- Issue provisional measures, with force of law;

- Perform other duties set forth in the Constitution

National Congress

Brazil's legislature is the bicameral National Congress (Portuguese: Congresso Nacional), which consists of the Senate (the upper house) and the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house).

The Federal Senate (Senado Federal) contains 63 seats: three senators from each State (including the Distrito Federal); the Chamber of Deputies (Câmara dos Deputados) comprises 310 deputies.

Elections for both are held regularly, however, only two parties have representation in the National Congress: the "official" party (National Renewal Alliance Party) and the "loyal opposition" party (Brazilian Democratic Movement), which are also the only two legal parties. The role and powers of Congress are severely circumscribed by the 1967 Constitution, effectively reducing it to a rubberstamp body.

Judiciary

The judicial branch is composed of federal, state, and municipal courts. The minimum and maximum ages for appointment to the superior courts are thirty-five and sixty-five; mandatory retirement is at age seventy. These federal courts have no chief justice or judge. The two-year presidency of each court is by rotation and is based on respecting seniority.

Brazil's highest court is the Federal Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal, or STF). Created in October 1890, the STF has eleven members appointed by the president. The STF decides conflicts between the executive and legislative branches, disputes among states, and disputes between the federal government and states. In addition, it rules on disputes involving foreign governments and extradition. The STF issues decisions regarding the constitutionality of laws, acts, and procedures of the executive and legislative branches, and warrants of injunction. The president of the STF is third in the line of presidential succession and would preside over an impeachment trial held by the Senate.

The TFR (Federal Court of Appeals) was created under the 1946 constitution. As the last court of appeals for nonconstitutional questions, the TFR reviews decisions of the TRFs (Regional Federal Courts) and tries governors and federal judges. The president appoints its members: One-third are picked from the ranks of TRF judges; one-third from the ranks of State Supreme Court judges; and one-third from the ranks of state and federal public prosecutors.

Brazil's judicial system has a series of special courts, in addition to the regular civil court system, covering the areas of military, labor, and election affairs. The Superior Military Court (Superior Tribunal Militar, or STM), created in 1808 by João VI (king of Portugal, 1816-26), is the oldest superior court in Brazil. It is composed of fifteen judges appointed by the president. Three members must have the rank of admiral in the Brazilian Navy (Marinha do Brasil), three must be general officers of the Brazilian Air Force (Fôrça Aérea Brasileira, or FAB), four must be army generals, and five must be civilians. The latter must be over age thirty and under age sixty-five. Two of the civilians are alternately chosen from among military justice auditors and military court prosecutors; three are lawyers with noted judicial knowledge and ten years of professional experience. The STM has jurisdiction over crimes committed by members of the armed forces. It is also used extensively to try civilians accused of crimes against "national security."

The government of Getúlio Vargas created the Superior Electoral Court (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, or TSE) in 1932 in an effort to end election fraud and manipulation. The TSE has jurisdiction over all aspects of elections and regulates the functioning of political parties. Its powers include supervising party conventions and internal elections; granting or canceling registration of parties; registering candidates and certifying those elected; regulating and supervising party access to free television and radio time during an election; and registering voters.

The TSE has seven members, each with a two-year mandate. By secret ballot, the STF chooses three of its members to sit on the TSE, and the STJ chooses two of its members. The president appoints two lawyers from among a six-name list submitted by the STF. The TSE elects its president and vice president from among the members of the STF.

The system of labor courts was created by Getúlio Vargas in the 1930s to arbitrate labor-management disputes, which previously had been settled by police action. The 1946 constitution created the Superior Labor Court (Tribunal Superior do Trabalho, or TST). The labor court system has jurisdiction over all labor-related questions. It registers labor contracts, arbitrates collective and individual labor disputes, recognizes official union organizations, resolves salary questions, and decides the legality of strikes. The president appoints twenty-seven judges to the TST. Seventeen of the judges - eleven career labor judges, three labor lawyers, and three labor court prosecutors - receive lifetime terms (to age seventy). Ten temporary judges are appointed from lists evenly divided between the confederations of labor and management.

The Public Ministry is an important independent body in Brazil's judicial system. Its principal component, the Office of the Solicitor General of the Republic (Procuradoria Geral da República, or PGR), is composed of several public prosecutors selected by public examination. The PGR's headquarters is in Brasília, and it has branches in every state. The PGR is charged with prosecuting those accused of federal crimes, those accused of offending the president and his ministers, and all federal officials and employees accused of crimes. The president has the power to appoint and dismiss the solicitor general at will.

Finally, the Office of the Federal Attorney General (Advocacia- Geral da União, or AGU) defends the federal government against lawsuits and provides legal counsel to the executive branch.

The judicial branch's powers are very limited. The 1967 Constitution, which removed all privileges previously enjoyed by judges, also granted the president the right to forcibly remove or retire judges if so chose. More than one judge has been subjected to removal or retirement for inefficiency or insufficient loyalty to the junta.

Cabinet

The composition of the current cabinet is as follows:

- Minister of Aeronautics: Sérgio Fortes

- Minister of Agriculture: Antônio Corrêa Prestes

- Minister of the Army: João Vieira Soares

- Minister of Communications: Vítor Ribeiro

- Minister of Education: Mário Rodrigues

- Minister of External Relations: Deodoro Cabral

- Minister of Finance: José Salazar

- Minister of Health: Francisco Pinheiro

- Minister of Industry and Commerce: Augusto Geisel

- Minister of Interior: Afonso Luiza Rezende

- Minister of Justice: Paulo Inácio dos Santos

- Minister of the Navy: Carlos Guimarães Rosa

- Minister of Transport: Fernando Cautiero e Silva

Constitution

After the coup d'état of 1964, the controllers of the new regime kept the 1946 constitution and promised to restore democracy as soon as possible. However, they eventually did not and were faced with a dilemma, as every measure they took was strictly against the current constitution, including the coup itself.

The so-called Institutional Acts issued by the president were, in practice, placed higher than the Constitution and could amend it – but they were not foreseen in the constitution, which made them illegal.

In 1967 the situation had come to a point that was unbearable: the military could not keep the farce of democracy any more and was eager to enable itself with "proper" laws to fight subversivos (anyone that opposed the regime). The constitution was denounced as "obsolete" as the "new institutions" were not foreseen in it.

A new constitution was written by a team of lawyers commissioned by Marshal Humberto de Alencar Castello Branco, then president, amended (under the instructions of Castello Branco himself) by the Minister of Justice, Carlos Medeiros Silva and voted as whole by the Brazilian Congress (already purged of most opponents of the status quo).

The main features of the new Constitution were:

- Restriction of political rights: free elections would only be held at state and county level, but not in federal territories or cities considered as of interest of national security for whatever reason (such cities were specified as those lying by the international border, state capitals, "important" industrial centers, university towns, jungle towns, towns close to power plants, mining sites, etc). About 500 cities/towns were listed, the largest and most important ones.

- Restriction of civil rights: any meeting, assembly, or gathering of people should be formal, must be previously authorized, and conducted under supervision. Unauthorized meetings would be disbanded by the police and participants sued (or imprisoned).

- Creation of a military police to patrol the cities and "provide public security", reducing the autonomy of the existing civilian police.

- Removal of all privileges of judges, allowing the president to force them to retire or to remove them.

- Disbanding of all political parties (which had existed for only twenty years) and creation of a bipartisan system comprising the official party, the National Renewal Alliance Party (ARENA), and the controlled opposition, the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB).

- Creation of an indirect election system (Colégio Eleitoral) to choose the president.

- Limitation of federated states' autonomy.

- Granting the president the right to issue decrees (Decretos-Lei) that would be binding after 30 days if the Congress "did not have the time" to vote on them.

In 1969 this already very restrictive Constitution was widely amended by the junta and made even more dictatorial. The 1969 amendment is sometimes regarded as another Constitution. It brought some extra tools for the regime:

- State of emergency

- Capital punishment

- Exile as punishment

- Suspension of habeas corpus

- Special military courts to try members of the military accused of crimes

- Transfer of command of the military police from each federal state to the Ministry of War

- Restrictions on travel

Economy

Brazil has pursued generally sound economic policies for two decades. Since the mid-1980s, the government has sold many state-owned companies, and privatization is continuing as of June 2008. The government's role in the economy is mostly limited to regulation, although the state continues to operate the Central Bank, "strategic" defense industries such as Engesa and Embraer, and national infrastructure (roads, railways, airports, ports and harbors). Brazil is strongly committed to free trade and has welcomed large amounts of foreign investment. Brazil's approach to foreign direct investment is codified in the country's Foreign Investment Law, which gives foreign investors the same treatment as Brazilians. Registration is simple and transparent, and foreign investors are guaranteed access to the official foreign exchange market to repatriate their profits and capital.

Brazil's taxes are among the lowest in the world. There is a 10% flat-rate income tax; a 15% tax on corporate income; and a 10% value added tax. No other forms of taxation exist in Brazil, and the government has continually cut taxes in concert with its reductions in government spending.

Banking in Brazil is characterized by stability, privacy and protection of clients' assets and information. The country's tradition of bank secrecy is codified in law. Only the Confederate States of Latin America (ECAL) has more laissez faire banking than Brazil.

The government does not set wages, prices, or interest rates. The Brazilian government consistently manages to balance the budget, and keeps inflation in check by minimizing the amount of currency printed. There is talk of converting to a gold standard, though the government will not confirm or deny this.

Brazil's lax regulations make it a profitable and popular destination for outsourcing, ensuring that both skilled and unskilled jobs are plentiful. For the few who cannot find jobs, public works programs and the armed forces provide employment opportunities.

Healthcare and social security have both been fully privatized, although the government still retains the Ministry of Health (which is now responsible mainly for ensuring Brazilian children are vaccinated, overseeing Brazil's anti-malaria program, and ensuring that public sanitation is maintained). The government ended its subsidies to agriculture in 1998 (the government's role in agriculture now is limited to regulating food quality, food inspection and safety, and consumer protection).

Education is free and compulsory for children, although the government has actively worked to decrease its role in this area, content to leave the running of schools to churches, families, and local communities; however, education remains closely scrutinized, and those who teach "subversive" topics face a heavy fine, imprisonment, or even exile.

Brazil trades extensively with most countries, though its largest trading partner, by far, is the ECAL.

The country's largest industries include motor vehicles, chemicals, lumber, aircraft, machinery, natural gas, hydropower, petroleum, tourism, and agriculture. Brazil is self-sufficient in energy production and does not rely on imports. Brazil is also the largest producer of coffee (by far) in the world.